CS 245 - Logic & Computation

TTH 10:00AM - 11:20AM

MC 4045

Stephen Watt

10% quiz | 20% assignments | 30% midterm | 40% final

Office Hours:

Lila Kari: TTh 2:30-3:30 pm

Stephen Watt: M 11-12am F 1-2pm

1 | Propositional Logic

1.1 | Introduction

What is Logic?

“this course is like a broken toaster”

Logic = the Science of Reasoning Syllogism = a kind of logical argument in which a proposition (conclusion) is inferred from 2 or more others (premises)

Logic and CS

Computers are built from electronic digital circuits, which are formed out of logic gates

- Logic is used to reduce the number of necessary logic gates

Applications

- Automated theorem proving (proof verifiers)

- Fully / semi automated techniques to analyze the behavior of reactive programs

- Databases (SQL) use first-order logic

- Programming

- Program specification

- Formal verification

Propositional logic

Studies logical relationships between propositions (true/false statements)

Some important logical arguments: Hypothetical Syllogism

- If p then q

- If q then r

- If p then r

Disjunctive Syllogism

- p or q

- Not q

- p

Modus Ponens (crossing the pond)

- If p then q

- p

- q

Modus Tollens

- If p then q

- Not q

- Not p

Atomic Propositions = Proposition symbols which can’t be further subdivided Compound Propositions = Obtained by combining several atomic propositions

Logical Connectives = or / and / not / if-then

- Convention: Stating a proposition in English implies it’s true

- Negation (not) - is the only unary connective

- Conjunction (and)

- Disjunction (inclusive or) - p q should be translated as “p or q, or both”

- Implication (if-then) - is the only non-symmetric connective. reversing it is the converse

- Equivalence (if and only if)

Dealing with imprecision and ambiguity

- ”Don’t leave animals in cars because they rapidly turn into ovens”

Translations from English to Logic

1.2 | Propositional Logic Syntax

Syntax of propositional language : atoms, formulas

Expressions

- Expressions = finite strings of allowed symbols

- Length = number of occurrences of symbols in an expression

- Empty expression = expression of length 0, denoted by

- Equal = two expressions that are the same

- Concatenating two expressions is denoted as

- If , then

- is a segment of

- If , then is a proper segment of

- If , then is an initial segment (prefix) and is a terminal segment (suffix) of

The set of formulas of

- is the set of expressions of that consist of a proposition symbol only

- is the set of formulas in , defined recursively as any previous formulas joined by

Generating and parsing formulas of

Parse Tree = used to analyze formulas

Theorem: Unique Readability Theorem Every formula in is of exactly one of the six forms: an atom,

Mathematical induction (review), structural induction

Principle of Mathematical Induction:

- Establish that property is true for 0

- Establish that

Structural Induction for Recursively Defined Sets

- Base case(s)

- (Composite) Inductive step: Show that the property holds after applying each recursive rule

Lemma 1: Every formula in has an equal number of left and right parentheses

Proof: We use structural induction Base Case: is an atom, and has 0 left and right parentheses

For the subcase of Inductive Step: Assume is Inductive Hypothesis: formula has property

For the other subcases IH: Formulas both have property To prove for has property . WLOG, consider :

Unique Readability Theorem

Proof: Use the following Claims

- The first symbol of a formula is either or a proposition symbol

- Every formula has an equal number of and (Lemma 1)

- If is a non-empty proper initial segment of a formula , then has more than

Assume that a formula can be of the following forms

- , where

- , where

Recall that means they are equal

- Assume which leads to a contradiction

- Assume which leads to a contradiction

- Assume . Deleting the first symbol yields . Thus, B is:

- strictly shorter than - a contradiction

- strictly longer than - a contradiction

- the same length as - which proves the statement

Algorithm for parsing formulas: Count the excess of over to determine the number of sub-formulas

Precedence rules and scope for connectives

Precedence order:

- not

- and

- or

- if

- iff

1.3 | Propositional Logic Semantics

Syntax vs semantics, truth valuations, truth tables

Syntax = the rules used for constructing formulas in Semantics = are concerned with meaning (atoms and connectives)

Truth valuation:

Satisfiability, tautologies, contradictions

Satisfied = Something is valued at 1 under the truth valuation Tautology = Something that’s always true Contradiction = Something that’s always false

Plato’s 3 essential laws of thought:

- Law of identity:

- Law of contradiction:

- Law of excluded middle:

Proving argument validity semantically

Tautological consequence \models

- Special case: Tautological equivalence (|=|)

Proving tautological consequence by truth tables

Bash it (takes a long time and grows exponentially) Disproving by counterexamples

Edge cases: An unsatisfiable set (contradiction) tautologically implies any formula! The empty set is satisfied under any truth valuation!

General method for proving argument validity (semantically)

Test A will give a positive result if and only if either virus X or virus Y is present. Test B will give a positive result if and only if virus Y or Z is present. If test C is positive, virus Y can be excluded. The patient reacts positively to all three tests. Prove that the patient has virus X and virus Z but not virus Y

Solution:

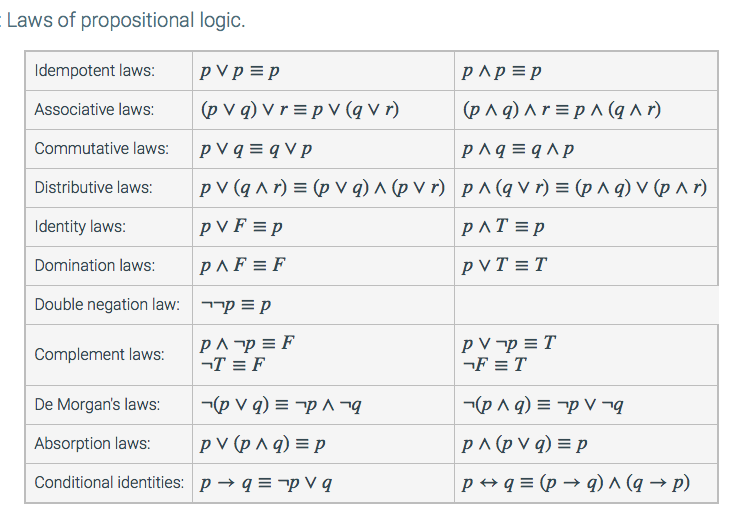

1.4 | Propositional Calculus: Essential Laws, Normal Forms

Propositional calculus

Simplification: Removing implication:

Removing if and only if: (both true or both false)

(first implies second or second implies first)

Essential laws for propositional calculus

- All laws come in dual pairs, which are obtained by swapping 0 and 1, as well as

- (somewhat shaky) Analogy: is treated like addition, while is treaded like multiplication

Absorption Laws I

Absorption Laws II

A literal is a formula of the form (complimentary literals)

Simplifying conjunctions (and)

- If an and contains 0, it always yields 0

- If an and contains 1 or any duplicate literals, they can be dropped

Simplifying disjunctions (or)

- If an or contains 1, it always yields 1

- If an or contains 0 or any duplicate literals, they can be dropped

Disjunctive / Conjunctive Normal Forms (DNF / CNF)

Def: Disjunctive Normal Form: A formula in DNF is of the form

where , and are literals for and . The formulas are the conjunctive clauses of the formula in DNF.

Def: Conjunctive Normal Form: A formula in CNF is of the form

Obtaining DNF and CNF from truth tables

Eliminate everything

1.5 | Connectives, Logic Gates, Circuit Design

n-ary connectives

Since , the connective is said to be definable in terms of

There are 16 binary connectives (there are -ary connectives)

Any set of connectives with the capability to express any truth table is said to be adequate

Proving adequacy and inadequacy of a set of connectives

Def: Adequacy A set S of connectives is called adequate iff any n-ary connective can be defined in terms of the connectives in S. For instance, the set is adequate

- Proving adequacy: Show that all connectives in an adequate set can be defined in terms of the connectives in

- Proving inadequacy: Show that one of the connectives in the adequate set cannot be defined using the connectives in

Pierce Arrow for NOR () is adequate

Sheffer stroke for NAND is also adequate

Ternary Connectives

- Define too mean if p, then q, else r

- There are distinct ternary connectives

Boolean algebra and propositional logic

Using set theory to describe propositional logic

Definition: Joolean algebra An -variable Boolean function is a function of the form

Logic Gates

Binary computers = transistors != electric computers

Circuit Design

Half-adder ( = sum, = carry)

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Full-adder (with the additional carry bit )

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Formula simplification and circuit minimization

Circuits can be simplified in the same way that code and logical formulas can

1.6 | Formal deduction in propositional logic

Formal deducibility in propositional logic

Formal Deducibility has a similar meaning to , signifying argument validity To write that is formally deducible (or provable) from , we write

11 rules of formal deduction (but I’m only writing the 3 coolest ones)

If , and , then (proof by contradiction)

If , and , then (proof by cases)

If , then (assumption of a premise is the antecedent of a conditional)

Definition of “formal deducibility”

Definition: Formal deducibility A formula is formally deducible from () if A is generated by a finite number of applications of the 11 rules of formal deduction

- Subsequent steps are generated by a rule of formal deduction

- The sequence of steps is called a formal proof of the last term

Checking a proof: Check each step Finding a proof: Work in reverse

Semantics vs Syntax:

- Tautological consequence is semantics

- Deducibility is syntax

Proving statements about formal induction: Use structural induction on the set of theorems

Theorems: Finiteness of premise set, reduction ad absurdum, transitivity

Theorem: Finiteness of premise set If , then there exists a finite

Theorem: Transitivity of deducibility Let .

Theorem: Reductio ad absurdum

Theorem of replaceability of Syntactically Equivalent Formulas

Definition: Two formulas are syntactically equivalent if

Theorem: Replaceability of syntactically equivalent formulas Let be syntactically equivalent. For any , let be constructed from by replacing some (not necessarily all) occurrences of by . Then are syntactically equivalent.

Theorems of Soundness and Completeness of Formal Deduction

Theorem: Soundness Theorem (should not be able to prove incorrect statements)

Theorem: Completeness Theorem (should be able to prove every correct statement)

Connection between syntax and semantics The Soundness and Completeness Theorems say that with formal deduction (as defined by the 11 rules) we can prove The truth, the whole truth, (completeness), and nothing but the truth. (soundness)

Logical Fallacies: Formal deduction can’t prove invalidity Recall that Descartes famously said “I think, therefore I am”. The joke was that Descartes goes into a bar and the bartender asks him if he wants another drink. “I think not,” says Descartes, and vanishes in a puff of smoke.

- Conclusion: (fallacy of affirming the consequent)

“Why are you standing on this street corner, waiving your hands?”

“I am keeping away the elephants.”

“But there aren’t any elephants here.”

“You bet: that’s because I’m here.”

- Conclusion: (fallacy of affirming the consequent)

Formal deduction proof strategies

- If the consequence is an implication is an implication (), use

- If one of the premises is a disjunction (), use proof by cases

- If we have to prove and the direct proof doesn’t work, proof the contrapositive

- If all else fails, use proof by contradiction or in the case of

Consistency and Satisfiability

Definition: Consistency A set of formulas is consistent (w.r.t. a system of formal deduction, herein ) if there is no formula such that and . Otherwise, is inconsistent.

Lemma: Satisfiability A set of logic formulas is satisfiable iff is consistent

Harry Potter and the 11 Rules of Formal Deduction

| symbols | rule | words |

|---|---|---|

| (Reflexivity) | ||

| If , then | (Addition of premises) | |

| If and then | ( elimination) or proof by contradiction | |

| If and then | ( elimination) modus ponens | |

| If , then | ( introduction) | |

| If then and | ( elimination) | |

| If and then | ( introduction) | |

| If and then | ( elimination) proof by cases | |

| If then and | ( introduction) | |

| If and then | ( elimination) | |

| If and then | ||

| If and then | ( introduction) |

1.7 | Automated Theorem Proving by Resolution

A formal deduction system with a single rule: resolution

Resolution theorem proving is a method of formal deduction

- ”a giga proof by induction”

- The only formulas allowed are disjunctions (OR)

- There is only one rule: resolution

- To prove that is valid, show that the following is not satisfiable

- Prove that from this set, we can derive both and

- Do this by converting everything to CNF

- The resolvent of is called the empty clause, signifying a contradiction

Example: Proving

Proof:

- (premise)

- (premise)

- (negation of conclusion)

- (resolving 1, 2 over )

- (resolving 3,4 over )

Proving argument validity with resolution

Resolution strategies

David Putnam Procedure (DPP)

Any clause corresponds to a set of literals (the literals contained in the clause). Thus, we can use set notation to express resolution: produces:

DPP:

- Remote all clauses with

- Choose a variable in one of the clauses

- Add all possible resolvents using resolution on

- Discard all clauses with

If in some step one resolves , the output is the empty clause (valid, empty backpack) If one never has such a pair, the output is no clause (invalid, no backpack)

Apply DPP to

- Eliminating gives

- Eliminating gives

- Eliminating gives

- Eliminating gives - the output is the empty clause, and this statement is una

Soundness and Completeness of DPP (proofs optional)

2 | First-Order Logic

2.10 | First-Order Logic

First-order logic

FoL elements: Domain, individuals, variables, functions, relations, quantifiers

Negating quantifiers

Nested quantifiers

2.11 | Syntax of First-Order Logic

FoL syntax

Propositional logic: formulas are recursively built starting from atoms (proposition symbols) by the 5 formation rules that describe the use of connectives First-order logic: Modelled as individuals with relationships

- Domain

- Terms

- Atomic formulas

- Formulas

Formal language of FoL () Equality symbol

Terms

is an individual or variable

FoL formulas

is the simplest formula that has a T/F value are formulas

Unique Readability Theorem for FoL

is the set of sentences

First-order languages

Ex: First order language of elementary number theory

- Equality relation: Yes

- Relation symbols: <

- Individual (constant) symbols: 0

- Function symbols:

2.12 | Semantics of First-Order Logic

First-order logic semantics

Valuations

Value of a term

Value of formulas

2.13 | Logical Consequence: Argument Validity

Logical consequence ()

Proving argument validity

(Universally) valid formulas

Proving that a formula is (universally) valid

Logical equivalence, Replaceability theorem

2.14 | Formal Deduction for First-Order Logic

Formal deducibility in FoL

Harry Potter and the 6 additional rules for formal deduction

| symbols | rule |

|---|---|

| If is a theorem then is a theorem | |

| If is a theorem and does not occur in then | |

| If is a theorem and does not occur in or in , then is a theorem | |

| If is a theorem then is a theorem where results from by replacing some (not necessarily all) occurrences of by | |

| If is a theorem and is a theorem, then is a theorem where results from by replacing some (not necessarily all) occurrences of by | |

| is a theorem |

Understanding the rules of formal deduction

Definition of formal deduction

Replaceability & Duality in formal deduction

Replaceability: If , we can replace with Duality: A formula is the same if we exchange , , and negate all atoms

Soundness and completeness

2.15 | Resolution for FoL and Automated Theorem Provers

Prenex Normal Form (PNF)

PNF = All quantifiers at the front

- No quantifiers also counts as PNF

Converting into PNF

- Eliminate all

- Move all negations inward (only as part of literals)

- Standardize the variables apart

- Move all quantifiers to the front

Preprocessing: Existential-free PNF

Skolem functions allow us to remove all existential quantifiers by replacing them with variables

When working with formulas in existential-free PNF, all variables are implicitly considered to be universally quantified

Preprocessing: Clauses

Sane as formal logic: Put everything in CNF

Valid arguments & satisfiability of a clause set

Clause unification & resolution for FoL

Unifying

Proving FoL arguments valid by resolution for FoL

3 | Decidability and Peano Arithmetic

3.16a | Computation and Logic: Turing Machines

What is an algorithm?

A finite sequence of well-defined, computer-implementable instructions, typically to solve a class of problems or perform a computation.

The Halting Problem

Halting Problem: Does there exist an algorithm (program) that operates as follows:

- Input: A program P , and an input I to the program.

- Output: “Yes” if the program P halts on input I, and “No” otherwise.

Proved unsolvable by Alan Turing

- Construct which calls and outputs the opposite of it’s result

- Then you cannot tell if halts

Turing Machines as a formal model of computation

A Turing Machine is a 7-tuple where

- = the finite set of states of the finite control

- = the finite set of input symbols

- = the set of tape symbols such that

- = the (partial) transition function such that , where L, R are “left” and “right”

- = the start state, a member of

- = the blank symbol, which is in but not

- = the set of final, or accepting states, a subset of

Language accepted as a Turing Machine

Can be graphs

Turing machines as computers of functions

Types of Turing Machines

Total Turing machine = halts on every input Universal Turing Machine = can simulate the computations of every TM

The Church-Turing Thesis

”Any problem that can be solved with an algorithm can be solved by a Turing Machine.”

- It was proved that a Turing Machine is equivalent in computing power to all other, most general, mathematical models of computation.

3.16b | Undecidability of Universal Validity for First-Order Logic

Decidability and computability

A decision problem for which there exists a terminating algorithm that solves it is called decidable (solvable), otherwise it is undecidable (unsolvable)

- Solvable means there exists a total TM that accepts those and only those problem instances that lead to a “yes” answer

A total function that can be computed by a total Turing machine is called computable, otherwise it is called uncomputable.

- Uncomputable function example: the Busy Beaver function

- Let be the max number of 1s that a TM with states and alphabet may print on a blank tape before halting

The satisfiability (is any set satisfiable) and universal validity (is any formula valid) problems for FoL are undecidable

Proving undecidability

Reduce it to a previously solved problem. Suppose you can reduce to :

- If is decidable, we can’t conclude anything

- If is undecidable, so is

- If is decidable, then so is

- If is undecidable, we can’t conclude anything

Examples of undecidable problems

decider = a total TM that solves a decision problem

Undecidability of universal validity of FOL formulas

3.17 | Application of FoL: Peano Arithmetic (successors)

Formal deduction proofs of properties of equality

Introducing a new kind of equality:

First-order languages (theories)

A set of domain axioms + a system of formal deduction = a theory

- Number / set / group / graph theory

- Euclidean geometry

- Computable functions (lambda calculus)

- Relational databases

Number theory (Peano Arithmetic)

Number theory

- Domain: natural numbers

- Addition

- Multiplication

- Ordering

Peano Arithmetic (PA) Symbols

- Individual (constant): 0

- Functions s (successor, ),

- Relation: equality Axioms

- Axioms defining the unary function successor and binary functions addition and multiplication

- Axioms for induction

Harry Potter and the 7 Axioms for Peano Arithmetic

- - negating the successor is false

- - successor is one to one

- - addition by 0

- - successor addition

- - multiplication by 0

- - successor multiplication

- - idk bruh

Proofs in Peano Arithmetic

- successor of a thing doesn’t equal the thing

- a natural number is 0 or has a predecessor

Defining new arithmetic relations

- iff

- iff

- iff

- iff

Godel’s Incompleteness Theorem

Godel’s Incompleteness Theorem: Any consistent formal theory T with a decidable set of axioms, and that is capable of expressing elementary arithmetic (e.g., Peano Arithmetic), is syntactically incomplete, that is, there exists a formula expressible in T that can neither be proved nor disproved in T .

Can be proved using a contradiction including the Halting Problem

4 | An important application of logic to CS

4.18 | Formal Verification

Introduction: What and Why?

Techniques for showing program correctness

- Inspection

- Testing:

- Black-box: tests independent of code

- White-box: tests based on code

- Formal design verification

Formal program verification:

- Formally state the specification of a program with FoL

- Prove that the program satisfies the specification for all inputs

- Although this is undecidable (no terminating algorithm), there are some techniques

Framework for formal verification

- Convert the English description of to logic ()

- Write a program meant to realize in some given programming environment

- Prove that the program P satisfies

Imperative programming: Defines control flow as statements that change a program states / describes how a program operators (FORTRAN, PASCAL, OOP languages) Declarative programming: Focuses on what the program should accomplish without telling it how to do it (SQL, functional programming, HTML)

We are verifying imperative (uses variables), sequential (no concurrency), and transformational (turns inputs to outputs) languages.

We use the core features of C/C++ and Java

- ints and bools

- assignment

- sequence

if-then-elseconditionalswhileloops

Pre- and Post-conditions

Hoare Triples:

- = precondition

- = program or code

- = postcondition

Specification is not behaviour

- Instead of , write

Partial and Total Correctness

Definition: Partial Correctness A Hoare triple is satisfied under partial correctness, denoted

if and only if an input satisfying given to terminates and satisfies

Partial correctness can be vacuously satisfied if the program never terminates

while true { x = 0; } // infinite loopDefinition: Total Correctness Partial correctness + every valid input terminates

If the input is altered (“consumed”), a program is satisfied under NEITHER partial nor total correctness

A Formal Proof System for Partial Correctness

Rewriting the pre and postconditions for correctness using FoL. Domain: Programs, program states, and conditions

State(s)- “s is a program state”Condit(P)- “P is a condition”Code(C)- “C is a program”Satisfies (s,P)- “State s satisfies condition P”Termiantes (C,s)- “Program C terminates when given state s”result (C,s)- A FUNCTION that gives the state resulting from executing C with state s if C terminates (undefined otherwise)

Expressing correctness with FoL (Hoare triple ) Partial correctness

Total correctness

Assignments

To prove partial correctness, use sound inference rules To prove termination, use ad-hoc reasoning (even though program termination is undecidable)

A partial correctness proof is an annotated program with justifications

Inference rule for assignment (assignment)

- If the condition(s) / Hoare triples above the line are proved, then the Hoare triple under the line holds

- This means ” will hold after substituting all values of for E”

- is read as “Q with E in place of x” (x is a free variable)

Example ()

We usually work backwards from the postcondition

Inference rules about implications (NOT FRACTIONS, BUT UNDERLINES)

Precondition strengthening (implied)

Postcondition weakening (implied)

Inference rules for instruction (composition)

- We find a midcondition Q for which we can prove the top (like transitivity)

Most proofs are constructed from the bottom upwards

Conditionals

(if-then-else)

(if-then)

Proof strategy

- Annotate the program using appropriate inference rules

- ”back up” the proof: add an assertion/condition before each assignment statement

- Prove any “implieds” (annocations from 1, assertions from 2)

While-Loops and Total Correctness

(partial-while)

- = loop invariant (true both before and after each execution of the body of the loop)